I’ve just started reading A Room of One’s Own (which I hope you knew without me telling you is by Virginia Woolf), and though I’m only a chapter in, I feel the need to blog about it.*

If you haven’t read it (I’m betting most people haven’t, as it’s unencouragingly dense with Woolf’s typical long-winded and tangential style), it’s basically a compilation of Woolf’s thoughts on woman writers of fiction, from what is necessary to be a woman writer (shock of shocks, one needs a room of one’s own) to the various obstacles facing female scholars.

By the end of the first paragraph, I was fairly overwhelmed by the fact that this issue being written about eighty-five years ago is still entirely relevant today—not necessarily to the same extent as Woolf was facing (in the U.S., at least), and certainly not only to the gender-spectrum she’s addressing here, but there were more parallels than I could stomach silently.

Those who have read Woolf will back me up when I say: Her narration has less to do with the action than with the stream-of-consciousness descriptions. ARoOO [1] is no exception. However! There is some sort of movement to the story, and that’s the main thing I’m going to talk about, since there’s a certain fairy tale morality-story structure to it.

If you haven’t read it (I’m betting most people haven’t, as it’s unencouragingly dense with Woolf’s typical long-winded and tangential style), it’s basically a compilation of Woolf’s thoughts on woman writers of fiction, from what is necessary to be a woman writer (shock of shocks, one needs a room of one’s own) to the various obstacles facing female scholars.

By the end of the first paragraph, I was fairly overwhelmed by the fact that this issue being written about eighty-five years ago is still entirely relevant today—not necessarily to the same extent as Woolf was facing (in the U.S., at least), and certainly not only to the gender-spectrum she’s addressing here, but there were more parallels than I could stomach silently.

Those who have read Woolf will back me up when I say: Her narration has less to do with the action than with the stream-of-consciousness descriptions. ARoOO [1] is no exception. However! There is some sort of movement to the story, and that’s the main thing I’m going to talk about, since there’s a certain fairy tale morality-story structure to it.

So, basically, VW is asked to give a lecture on women in fiction (truth—that’s the origin of the papers that morphed into this). She goes for a walk in Oxbridge (the fictional conglomeration of the U.K.’s most prestigious/hoity-toity universities) to ponder over what this lecture should encompass. Capiche?

In her pondering, she gets all worked up over something and strays from the neat little footpath: “I found myself walking with extreme rapidity across a grass plot. Instantly a man’s figure rose to intercept me” (6) This man turns out to be a Beadle, which if you don’t know is “a minor official who carries out various civil, educational, or ceremonial duties” (Wikipedia). So he pops up from the lawn, making wild gesticulations at her and basically freaking the fuck out:

In her pondering, she gets all worked up over something and strays from the neat little footpath: “I found myself walking with extreme rapidity across a grass plot. Instantly a man’s figure rose to intercept me” (6) This man turns out to be a Beadle, which if you don’t know is “a minor official who carries out various civil, educational, or ceremonial duties” (Wikipedia). So he pops up from the lawn, making wild gesticulations at her and basically freaking the fuck out:

His face expressed horror and indignation. Instinct rather than reason came to my help; he was a Beadle; I was a woman. This was the turf; there was the path. Only the Fellows and Scholars are allowed here; the gravel is the place for me. (7)

Why, if it isn't a Gatekeeper!

VW’s just like “chill, dude,” and turns back to the footpath, concluding that “though turf is better walking than gravel, no very great harm was done” (7). Basically, the usual reaction to a small amount of oppression—it’s inconvenient, but she puts up with it to keep the peace.

VW’s just like “chill, dude,” and turns back to the footpath, concluding that “though turf is better walking than gravel, no very great harm was done” (7). Basically, the usual reaction to a small amount of oppression—it’s inconvenient, but she puts up with it to keep the peace.

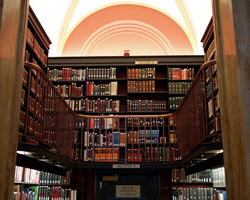

like a guardian angel barring the way with a flutter of black gown instead of white wings, a deprecating, silvery, kindly gentleman, who regretted in a low voice as he waved me back that ladies are only admitted to the library if accompanied by a Fellow of the College or furnished with a letter of introduction. (9)

I mean, what the hell, man, amirite? Sure, this guy’s all dignified and whatnot, and he’s a “kindly gentleman,” so he doesn’t seem malevolent or mean-spirited or whatever, but he won’t let her into the fucking library unless she jumps through a bunch of ridiculous hoops that some frakkin’ Fellow (who probably doesn’t appreciate Milton or Lamb or any of those library-contents nearly as much as VW does) can get into scot-free.

So yeah, VW’s pretty pissed now. But all her anger’s useless: “That a famous library has been cursed by a woman is a matter of complete indifference to a famous library” (9). So she just walks away. Because she’s classy like that.

From there, she hears a chapel organ banging away nearby, and goes to see what’s up. A bunch of old dudes in robes and whatnot are having some pomp and circumstance, and she’s just like “Y’know what? Screw that noise” (literally, as the case may be):

So yeah, VW’s pretty pissed now. But all her anger’s useless: “That a famous library has been cursed by a woman is a matter of complete indifference to a famous library” (9). So she just walks away. Because she’s classy like that.

From there, she hears a chapel organ banging away nearby, and goes to see what’s up. A bunch of old dudes in robes and whatnot are having some pomp and circumstance, and she’s just like “Y’know what? Screw that noise” (literally, as the case may be):

I had no wish to enter had I the right, and this time the verger might have stopped me, demanding perhaps my baptismal certificate, or a letter of introduction from the Dean. (10)

She’s learned from her earlier experiences, and, as with any outcast, has decided to reject the Good Old Boys before they get a chance to reject her. Sound familiar?

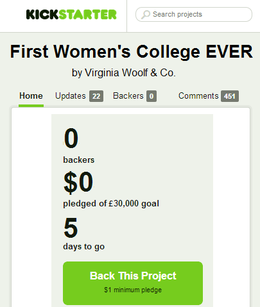

One thing leads to another, and VW ends up in a meeting with some of her compatriots about founding a college for women [2]—they want a lawn they can meditate on and a library they can go into, and when it comes down to it they wouldn’t mind some robes and pomp and circumstance, either. Their greatest dilemma in all this is how to pay for it. They’d worked out that they need £30,000 for the endeavor:

One thing leads to another, and VW ends up in a meeting with some of her compatriots about founding a college for women [2]—they want a lawn they can meditate on and a library they can go into, and when it comes down to it they wouldn’t mind some robes and pomp and circumstance, either. Their greatest dilemma in all this is how to pay for it. They’d worked out that they need £30,000 for the endeavor:

not a large sum, considering that there is to be but one college of this sort for Great Britain, Ireland and the Colonies, and considering how easy it is to raise immense sums for boys’ schools. But considering how few people really wish women to be educated, it is a good deal. (Lady Stephen, Emily Davies and Girton College (1927), 150-1)

These are the days before Kickstarter, so options are limited, but all of their potential financiers who believe in the project happen to be women, and, well, women don’t have any money.

She goes into some detail here about why women don’t have any money, mourning “What had our mothers been doing then that they had no wealth to leave us? Powdering their noses?” (26)—the laws enabling a woman to keep the money she earned were only made some 58 years ago, and those allowing a woman to inherit more recently than that.

Even though those laws have now been passed for years, women continue to suffer from the effects of their lack—since women couldn’t earn money, they had no reason to work for it, and so even once they could earn it they still hardly even did; now that they can have incomes, they need an education in order to have a desirable job, yet are not allowed into the establishments that would provide said education; and they cannot found their own such establishment without the funding they cannot work to have.

I ask again: sound familiar?

Reading this story about a woman in 1928 faced with all of these obstacles, I am struck by the echoes felt in obstacles that face us (“us” here meaning not only women, but every marginalized demographic) here in “modern” society. Eighty-five years later, there may not be many establishments that will refuse entry to a person based on the color of their skin or what’s between their legs (none, legally), but there are plenty of other ways to make folks feel unwelcome.

When a woman posts a picture of herself on the internet that is “stolen and turned into a fat-shaming anti-feminist meme on Facebook,” that is the bigoted Beadles of the 21st century freaking out over a woman not fitting their small-minded ideals and trying to scare her off the grass.

When a professor declares John Green (a white guy) as “the revolutionary who brought back the young adult novel,” effectively erasing female YA novelists from the history of his canon and selectively forgetting their contributions to the popularity of the genre (oh, nice to meet you, Ms. Rowling, Ms. Meyer, and Ms. Collins--not to mention goddamn Judy Blume who founded the fucking genre by writing about teen sexuality in the 1970s when it was beyond taboo I mean really people), that is the polite gentleman slamming the doors of Literature on them.

Whenever a woman considers cosplaying at a convention for something she’s passionate about, but remembers the hue and cry over “fake geek girls” who “just want attention” and chooses to go in plainclothes (or not at all), she is channeling Woolf’s tired turn away from the scholars in their robes.

And all the wonderful movie heroines who will never see the big screen because Hollywood has deemed movies about women destined to flop and thus unworthy of the money spent to make them—well, those ladies are ol’ VW and her pals, sittin’ around wishing someone with cash would take the chance on investing in them, for once.

No matter the century, no matter the country, no matter the marginalized party [3], the systems of oppression are always the same.

She goes into some detail here about why women don’t have any money, mourning “What had our mothers been doing then that they had no wealth to leave us? Powdering their noses?” (26)—the laws enabling a woman to keep the money she earned were only made some 58 years ago, and those allowing a woman to inherit more recently than that.

Even though those laws have now been passed for years, women continue to suffer from the effects of their lack—since women couldn’t earn money, they had no reason to work for it, and so even once they could earn it they still hardly even did; now that they can have incomes, they need an education in order to have a desirable job, yet are not allowed into the establishments that would provide said education; and they cannot found their own such establishment without the funding they cannot work to have.

I ask again: sound familiar?

Reading this story about a woman in 1928 faced with all of these obstacles, I am struck by the echoes felt in obstacles that face us (“us” here meaning not only women, but every marginalized demographic) here in “modern” society. Eighty-five years later, there may not be many establishments that will refuse entry to a person based on the color of their skin or what’s between their legs (none, legally), but there are plenty of other ways to make folks feel unwelcome.

When a woman posts a picture of herself on the internet that is “stolen and turned into a fat-shaming anti-feminist meme on Facebook,” that is the bigoted Beadles of the 21st century freaking out over a woman not fitting their small-minded ideals and trying to scare her off the grass.

When a professor declares John Green (a white guy) as “the revolutionary who brought back the young adult novel,” effectively erasing female YA novelists from the history of his canon and selectively forgetting their contributions to the popularity of the genre (oh, nice to meet you, Ms. Rowling, Ms. Meyer, and Ms. Collins--not to mention goddamn Judy Blume who founded the fucking genre by writing about teen sexuality in the 1970s when it was beyond taboo I mean really people), that is the polite gentleman slamming the doors of Literature on them.

Whenever a woman considers cosplaying at a convention for something she’s passionate about, but remembers the hue and cry over “fake geek girls” who “just want attention” and chooses to go in plainclothes (or not at all), she is channeling Woolf’s tired turn away from the scholars in their robes.

And all the wonderful movie heroines who will never see the big screen because Hollywood has deemed movies about women destined to flop and thus unworthy of the money spent to make them—well, those ladies are ol’ VW and her pals, sittin’ around wishing someone with cash would take the chance on investing in them, for once.

No matter the century, no matter the country, no matter the marginalized party [3], the systems of oppression are always the same.

Endnotes:

* I’ve lately been keeping a close eye on #DiversityInSFF, which has been trending on twitter ever since Jim C. Hines got the ball rolling last week. So variations on this topic have been on my mind rather a lot.

[1] Yup, the initialism of A Room of One’s Own is also the onomatopoeia of a wolf’s howl. Said animal happens to be homophonous with VW’s last name. Oh, the chortles!

[2] Disclaimer! Plenty of women's colleges existed before the 1920s, so either I misread this passage (were they wanting a co-ed one?) or Woolf was speaking metaphorically for women throughout the ages struggling to find a place in academia (which would be in keeping with her style throughout). I'm leaning toward the latter (because I don't like to be wrong), but can admit my own imperfections in this area. Anyway, this essay is in response to my reading of ARoOO, not to the actual historical events.

[3] I do realize that all of my examples were of sexism; it seemed easier to stick to the closer parallel, but obviously there are plenty of similar stories in relation to racism, homophobia, classism, etc.

Works Cited:

Unless otherwise stated or linked, all quotations and page numbers are from Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own; my edition was published with Three Guineas by Oxford University Press in 2008. (For more info on it, see ISBN: 978-0-19-953660-3.)

* I’ve lately been keeping a close eye on #DiversityInSFF, which has been trending on twitter ever since Jim C. Hines got the ball rolling last week. So variations on this topic have been on my mind rather a lot.

[1] Yup, the initialism of A Room of One’s Own is also the onomatopoeia of a wolf’s howl. Said animal happens to be homophonous with VW’s last name. Oh, the chortles!

[2] Disclaimer! Plenty of women's colleges existed before the 1920s, so either I misread this passage (were they wanting a co-ed one?) or Woolf was speaking metaphorically for women throughout the ages struggling to find a place in academia (which would be in keeping with her style throughout). I'm leaning toward the latter (because I don't like to be wrong), but can admit my own imperfections in this area. Anyway, this essay is in response to my reading of ARoOO, not to the actual historical events.

[3] I do realize that all of my examples were of sexism; it seemed easier to stick to the closer parallel, but obviously there are plenty of similar stories in relation to racism, homophobia, classism, etc.

Works Cited:

Unless otherwise stated or linked, all quotations and page numbers are from Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own; my edition was published with Three Guineas by Oxford University Press in 2008. (For more info on it, see ISBN: 978-0-19-953660-3.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed